The “Christian Nationalist” Mirage

A lot of rhetoric and a dash of logical fallacy concoct an imaginary menace.

If the label “Christian nationalism” means nothing to you, you are, according to a Pew Research poll published in October 2022, part of the majority:

Overall, 45% of Americans say they have heard at least a little about Christian nationalism, including 5% who have heard or read a great deal about it, 9% who have heard quite a bit, 17% who have heard some and 14% who have heard a little.

Interestingly, familiarity with the concept is lowest among the people whom you would expect to find it most simpatico, namely, Christians:

Non-Christians are more likely than Christians to be familiar with the term (55% vs. 40%), with atheists (78%) and agnostics (63%) being the most familiar.

Only three percent of Christians say that they have a “great deal” of familiarity; another six percent have “quite a bit”. On the other hand, 22 percent of the religiously unaffiliated and 43 percent of atheists claim that they fall into the two most knowledgeable categories.

Christians who have heard of Christian nationalism view it unfavorably by a two-to-one margin. Overall, only five percent of all Americans and seven percent of Christians hold a favorable opinion. So far as I can determine, the Christian nationalist caucus in Congress has only one member, the eccentric (to use the most charitable adjective available) Marjorie Taylor Greene. There are a handful of intellectuals who have written tracts advocating Christian nationalism of some kind. Their authors are obscure academics whose works, as one reviewer put it, “will be of interest only to a handful of idiosyncratic, patriarchal Calvinists who are not particularly interested in the United States”.

Yet, according to a flurry of books and articles and even a new film produced by Rob Reiner, this ideology that most Americans haven’t heard of and only a tiny sliver favor controls the Republican Party and molds the beliefs of a large proportion – perhaps a majority – of the country. John Zmirak, author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to Catholicism, furnishes a summary of what’s afoot:

There’s a full-on propaganda campaign underway, with massive funding from hostile billionaires and malevolent “charities” that also fund Planned Parenthood, to portray Christians who want to save babies from killing and kids from castrating surgeries as quasi-Nazi bigots who don’t deserve to vote. The Stream already covered God & Country, the Rob Reiner film which tries to scare Christians into abandoning public witness on moral issues, as The Birth of a Nation helped the Ku Klux Klan scare black Americans away from the polls at elections.

A pair of sociology professors, Andrew L. Whitehead (who also appears in the Rob Reiner movie) and Samuel L. Perry, in their book Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, claim that “over half of the United States population embraces Christian nationalism to some extent”, which makes it sound menacing indeed.

Unlike many critics of Christian nationalism, Whitehead and Perry try to define the term rather than merely polemicize against it:

Simply put, Christian nationalism is a cultural framework – a collection of myths, traditions, symbols, narratives, and value systems – that idealizes and advocates a fusion of Christianity with American civic life. But the “Christianity” of Christian nationalism is of a particular sort. We do not mean Christianity here as a general, meta-category including all expressions of orthodox Christian theology. Nor will we use terms such as “evangelicalism” or “white conservative Protestantism” (to the extent that these represent certain theological-interpretive positions) as synonyms for Christian nationalism. On the contrary, the “Christianity” of Christian nationalism represents something more than religion. As we will show, it includes assumptions of nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity, along with divine sanction for authoritarian control and militarism. Understood in this light, Christian nationalism contends that America has been and should always be distinctively “Christian” (reflecting this fuller, more nuanced sense of the term) from top to bottom – in its self-identity, interpretations of its own history, sacred symbols, cherished values, and public policies – and it aims to keep it that.

A mass movement embracing nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, authoritarian control and militarism sounds quite unpleasant. (“Heteronormativity”, on the other hand, is just scientific fact and also rather essential to the continuance of the human species.) Whitehead and Perry warn their readers that this noxious stew isn’t the sustenance of a negligible minority. They present what they regard as convincing empirical evidence that roughly half the country can be classified as “ambassadors” for, or “accommodators” of, Christian nationalist views.

Their evidence comes from a survey that asked whether and how strongly (on a “0” to “4” scale) respondents agreed with these six propositions:

The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation.

The federal government should advocate Christian values.

The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state.

The federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public spaces.

The success of the United States is part of God’s plan.

The federal government should allow prayer in public schools.

Christian nationalists were presumed, quite reasonably, to agree with all of these statements except the third. Here are the results:

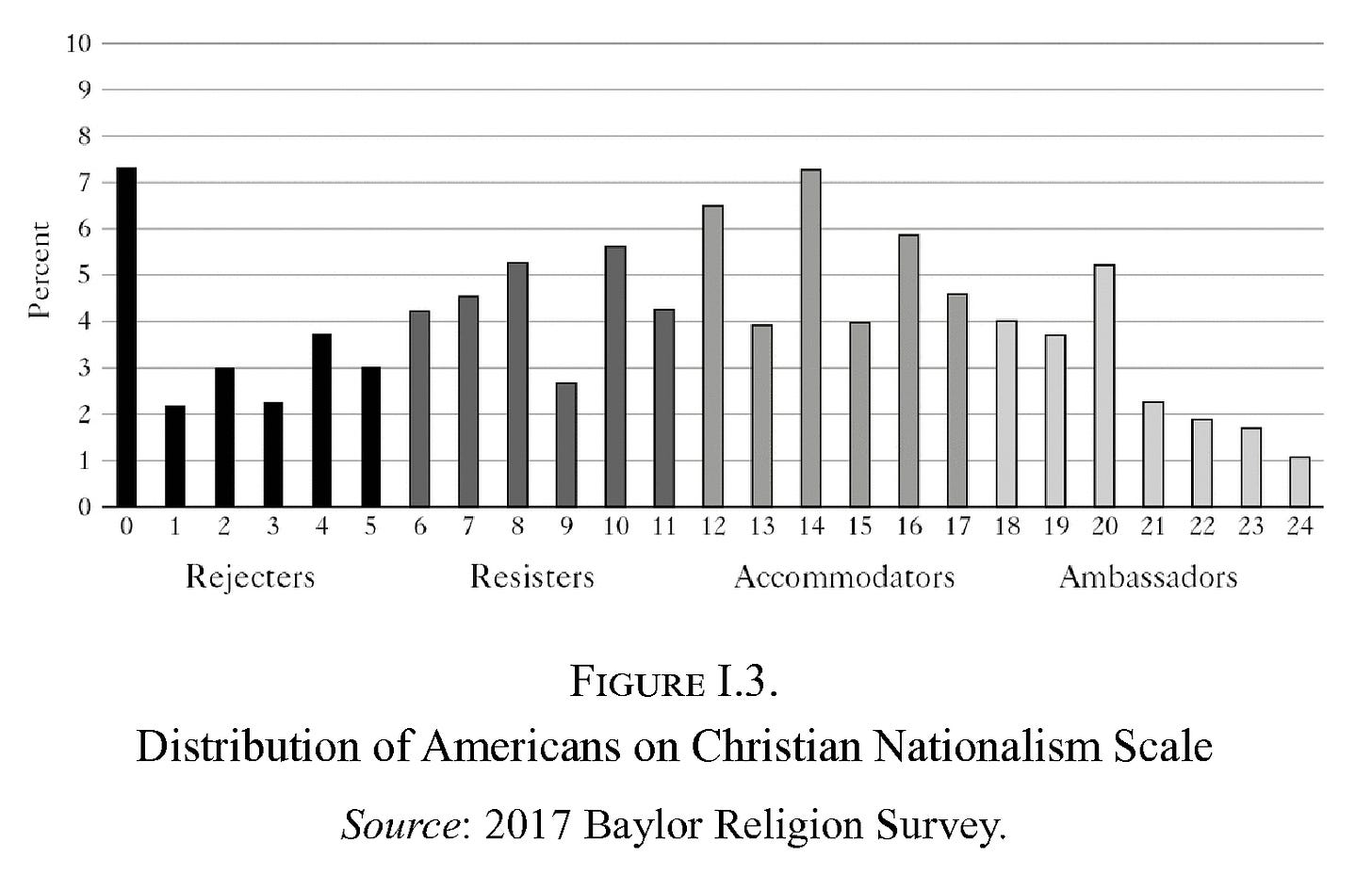

A whole one percent got a score of “24” by giving every presumed Christian nationalist position a “4”. The most common scores (slightly over seven percent each) were zero and 14. Just about exactly equal numbers fell to the left and the right of the Laodicean median score of 12. The conclusion that flows naturally from these data is that most Americans don’t have strong opinions about these supposedly diagnostic positions.

But even if some huge percentage of the country were 24’s, would it follow that they fit within the authors’ concept of Christian nationalism? Can one logically leap from support for government advocacy of “Christian values” (which include, let us remember, the Golden Rule and the Sermon on the Mount) to “nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity, along with divine sanction for authoritarian control and militarism”?

The logical mistake here should be apparent even to a sociologist. Professors Whitehead and Perry are guilty of the “fallacy of the undistributed middle”, the erroneous conclusion that two classes are identical because they share some characteristic. “All men are mortal. All dogs are mortal. Therefore, all men are dogs.”

Let me illustrate with a different set of propositions:

The rich don’t pay their fair share of taxes.

Corporations should serve significant purposes other than making profits for shareholders.

Government regulation of markets is essential to preventing domination by monopolies.

The government should do more to promote economic equality.

Economic progress has been largely the product of government action.

Labor unions are necessary to protect workers from exploitation.

Asked to rate agreement with those statements on a zero to four scale, a dogmatic communist would score very high, but so would a great many run-of-the-mill liberals. Would it be rational to conclude that a large proportion of the American public can be labeled “accommodators” or “ambassadors” of communism?

Returning to Whitehead and Perry’s “Christian nationalism” chart, it seems safe to assume that Lenin, Stalin and Mao would be “Rejecters”, probably with perfect zeros. Should we infer that the seven percent of poll respondents who got that score are convinced totalitarians and approve mass murder?

The orchestrated campaign against a Christian nationalism that barely exists isn’t a response to a palpable threat. Rather, it is an effort by woke progressives to avoid the hard work of arguing for their views by attaching nasty epithets to their critics. That tactic differs from McCarthyism in one respect: Communists were real and worked for a powerful, nuclear-armed enemy nation. Christian nationalists are rather like the luminiferous aether of pre-Einstein physics: supposedly all-pervading but impossible to detect.

John Zmirak, in the piece linked above, has this sensible suggestion for responding to inquisitors searching for Christian nationalist heretics:

If someone actually asks you whether you are a “Christian Nationalist,” there are several things you could say – depending on whether you thought the person sincerely confused or deluded, or instead was trying to trap you as the Pharisees tried to trap Jesus. Here are a few sample responses, for use in different contexts, to the question, “Are you a … Christian Nationalist?”

“Are you a pagan globalist? Just wondering.”

“That’s a hate-mongering dog-whistle, like Josef Goebbels’ made-up slur ‘Judeo-Bolshevik.’ Would you ask a Jewish person if he were one of those?”

“I believe that Natural Law, revealed to everyone Christian or not, ought to undergird all our laws. I learned that from reading Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’ Do you think he was wrong? The Nazis did. They persecuted people for promoting Natural Law.”

“I’m a patriotic Christian, like George Washington, Franklin Roosevelt, Billy Graham, and Pope John Paul II. What do you think I should be instead?”

Of course, the people who ask that question most determinedly don’t want to hear your answer.