A Vote for “First Past the Post”

Like democracy, it is the worst system imaginable, except for all the rest.

Searchers for silver linings have pored over the outcome of Britain’s Fourth of July election, which will go down in history as that nation’s second greatest debacle on the aforesaid date. The Labour Party, an aggregation of technocrats and lunatics, won 411 of 650 seats, a gain of 214. That was the dark cloud. The silver lining was that its 62.3 percent of seats was the product of a 33.8 percent share of the popular vote, not much larger than the 32.1 percent that it polled in the previous election in 2019. And the July 4th victory was tainted with apathy: The number of votes cast for Labour declined by over half a million.

Disproportionately good results for Labour imply disproportionately bad results for some other party. In this instance, the sufferer was Reform, the Conservative Party’s upstart rival, which won 14.3 percent of the votes but only five seats. By contrast, the other “major” minor party, the Liberal Democrats, with a vote share of 12.2 percent (only slightly higher than in 2019), increased their number of seats from eight to 72. Nigel Farage, Reform’s leader, has all at once become an advocate of replacing Britain’s “first past the post” (“FPTP”) system with proportional representation (“PR”).

The 2024 election was certainly adverse to the interests of Mr. Farage and his party. If Reform had been granted Parliamentary seats in proportion to its share of the vote, Mr. Farage would lead the third largest contingent in the House of Commons and would be much nearer to his ambition for Reform: displacing the Conservative Party as the major force on the Right.

Still, the purpose of elections is to serve the interests of the public rather than the politicians. In a democracy, an electoral system has two objectives. One is to ensure, to the extent possible, that government is responsive to the will of the governed. The other, also important, is to deliver a government that can actually govern.

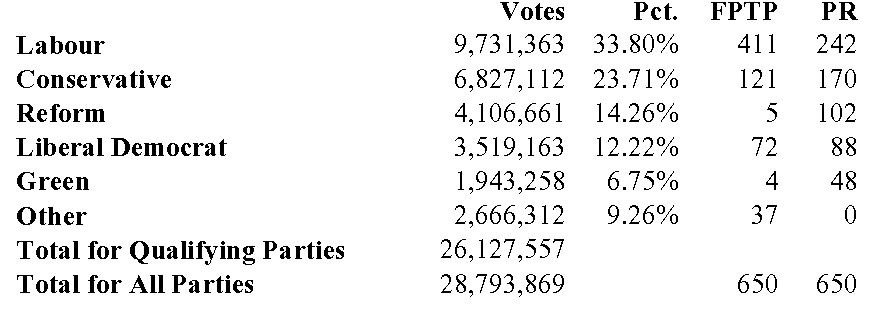

Let’s look at how well the real first past the post system and a hypothetical proportional representation system would serve those goals in Britain in 2024. There are a lot a PR systems. We’ll posit a simple version: Seats are allocated in proportion to vote shares, with the caveat the a party must gain at least five percent of the vote in order to be represented at all. Ballots cast for parties that don’t cross the five percent threshold are ignored. On that basis, the real and the hypothetical Parliaments look like this:

In the FPTP Parliament (the real-world one), Labour has a secure majority, 85 seats more than it needs. In the PR Parliament, it is the largest party but 84 seats short of a majority. Forming a government would require a coalition: either a shaky Labour-Lib Dem alliance (330 seats) or a larger but more fractious assemblage of Labour, Lib Dems and Greens (378 seats).

An ineffective left-wing government might be better for Britain than an effective one, but PR works both ways. In the 2019 Parliamentary election, the Conservative Party’s 43.6 percent of the vote yielded a comfortable majority, 365 seats. The overriding issue in that election was independence from the European Union, which all of the other significant parties and a fraction of Conservative MP’s opposed. Under our hypothetical PR system, only three parties would have been entitled to seats. The apportionment would have been along the lines of 324 or 325 Conservative, 239 Labour and 86 or 87 Lib Dem – not enough to enact Brexit or even to form a viable government.

What we have just hypothesized would have been the normal course of history if Britain in fact used PR. Since World War II, no party has won a majority of the popular vote in any Parliamentary election. The last time that one topped 45 percent was in 1970. Under a PR system, minority governments and coalitions would have been the rule. In real life, they have been exceedingly rare. Only three post-war general elections (February 1974, 2010 and 2017) have failed to produce a majority party.

What benefits does PR bring to offset its drawbacks? One could say that it reflects the mindset of the electorate. Most voters in most countries have only a hazy concept of what they want their governments to do, and the most popular policy ideas on both the Left and the Right tend to be simplistic if not screwy. Similarly, coalition governments tend to be puddings without themes – e. g., the current “traffic light” coalition in Germany (Social Democrats, Greens, and Free Democrats) – in which the influence of minor parties with idées fixes – e. g., the Green traffic light – is magnified. Alternatively, a niche party may find office holding so attractive that it stops pushing the ideas that make it distinctive. (The Free Democrats, classical liberals who constitute the “yellow” in the German traffic light, have done nothing much to slow their country’s slide toward climate cult socialism.)

Let us conclude by looking ahead. Politics is not a tableau but a motion picture. As soon as “cut” sounds for one scene, all thoughts turn to the next.

The script for the British PR movie has predictable plot points:

Remain, having achieved a respectable position as the third largest party in Parliament, would have no incentive to melt back into the Conservative fold. The internecine war on the Right would continue.

Labour, being dependent upon the Liberal Democrats for its majority, would have a strong incentive to cater to the Lib Dem idée fixe, namely, restoration of a single market with the EU. Revoking Brexit probably wouldn’t be on the table; the Conservative victory in 2019 was due largely to strong pro-Leave sentiment among traditional Labour voters. But a Labour-Lib Dem coalition might well seek some arrangement that avoided formal return to the bureaucrat-run European super-state but had the same de facto effect.

If the coalition solidified its majority by adding the Greens, it would naturally have to embrace their paradigmatic idée fixe, rolling back the Industrial Revolution, and perhaps their newer enthusiasm, strident demonization of Israel.

Labour would also have to be concerned with the burgeoning Moslem vote. In the real election, Muslim Voice, a “shadow political party”, won as many seats as Reform. PR would doubtless have awarded it many more. The Labour Party itself has a sizeable Jew-hating component. While Prime Minister Starmer has taken steps to stifle antisemitism within the party’s ranks, that would be harder to do if he led a coalition that either had a centimeter-wide majority or relied on Green support.

In the real, FPTP world, the primary motive underlying Labour’s policies will be its desire to win the next election. History shows that a huge majority in the present is no guarantee of future success. The Labour Prime Ministers who have lasted the longest – Tony Blair is the most recent exemplar – have watered down their party’s commitment to socialism. The incoming Labour government will doubtless do many foolish things, but, unlike its PR counterpart, it will have no reason or need to do unpopular foolish things.

Surprising as it may sound to American ears, Labour ran as a “law and order” party, denouncing cutbacks in police force budgets, the £200 threshold for taking action against shoplifting offenses, and the widespread practice of releasing prisoners early for want of facilities to hold them. Labour’s election manifesto also promised to increase defense spending to 2.5 percent of GDP, restrain expenditures for the “green transition” (albeit without abandoning unattainable green goals), and establish a Border Security Command to crack down on illegal immigration. The newly appointed Health Secretary has promised to “implement the expert recommendations of the Cass review”, which rejected such “gender-affirming” practices as castration, mutilation of secondary sex characteristics and administration of puberty blockers to children.

Those gestures toward sanity don’t prove that Labour’s red heart is becoming tinged with blue. (Remember that those colors have opposite connotations in Britain and America.) Much else that Labour supports is standard progressive balderdash, a mélange of tax increases, quasi-fascist industrial policy and utopian social theory. Also included in the manifesto is a commitment to recognizing a Palestinian state whether or not it is willing to make peace with Israel. The stew as a whole is a mediocre dish, but it is better than what one would get from a PR-created coalition.

In sum, the fault of First Past the Post, as illustrated by the British case, is that winning an election usually requires getting the most votes but not necessarily more than fifty percent. The fault of Proportional Representation, as illustrated almost everywhere that it is used, is that it strongly favors coalitions, and a coalition cannot survive unless it makes concessions to its least popular and most intransigent members. The will of the voters matters much less than backroom horse trading. PR may be “fairer” in some abstract sense, but it fails by the important criterion, producing effective government responsive to the people.